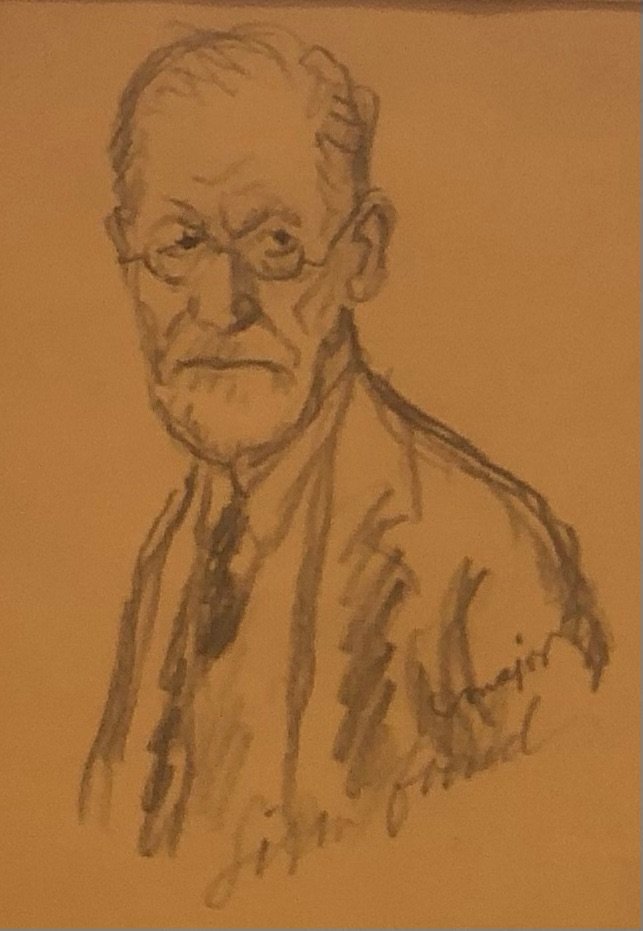

Freud, “The Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924) (III)

We have been considering the opening paragraphs of “Economic Problem,” in which Freud suggests that masochism is “mysterious from the economic point of view” (413). In the last entry, we objected that — in fact — Freud underscores masochism’s violation of the (non-economic) “pleasure principle,” rather than the (narrowly economic) “constancy” or “Nirvana” principle. And this is to say: it is not immediately obvious that, and how, masochism represents an “economic” problem at all.

As I suggested, though, Freud can speak in the way he does because, until the time of his article, students of psychoanalysis had imagined the two principles as equivalents. For the reader in 1924, in other words, any violation of the pleasure principle was ipso facto a violation of the constancy principle, hence for that reason an economic problem, after all. As I wrote in the last entry: to seek pain, on this conception, is to excite the very “stimulation” it is the proper task of mind to subdue. In such a situation, masochism really would qualify as a narrowly “economic” problem.

This equivalence was all but codified in “Drives and their Fates” (1915). In this place, Freud defends a “postulate” that we have no trouble recognizing as the “constancy” or "Nirvana” principle:

“[T]he nervous system is an apparatus which has the function of getting rid of the stimuli that reach it, or of reducing them to the lowest possible level; or which, if it were feasible, would maintain itself in an altogether unstimulated condition.” (120)

Freud explicitly relates this “constancy” postulate — one which “assign[s] to the nervous system the task…of mastering stimuli” (120) — to the “pleasure principle” as follows:

“When we further find that the activity of even the most highly developed mental apparatus is subject to the pleasure principle, i.e. is automatically regulated by feelings belonging to the pleasure-unpleasure series, we can hardly reject the further hypothesis that these feelings reflect the manner in which the process of mastering stimuli takes place — certainly in the sense that unpleasurable feelings are connected with an increase and pleasurable feelings with a decrease of stimulus.” (120-121)

Freud’s position in 1915, then, was that feelings of pleasure and unpleasure reflect, in a fairly straightforward way, the “economics” of inner stimuli and their management. In particular, decreases of “excitation” are pleasurable; increases are unpleasurable. Or again: the economic or “objective” task of the mental apparatus, to diminish excitation, is mirrored in the the organism’s “subjective” task of seeking pleasure and avoiding unpleasure. Indeed, it seems to follow that there is really only one principle — seen either under its “third-personal” or “first-personal” aspects.

In fact, as late as Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud appears still to be satisfied with this rough equivalence between the two principles:

“The dominating tendency of mental life, and perhaps of nervous life in general, is the effort to reduce, to keep constant or to remove internal tension due to stimuli (the “Nirvana principle,’ to borrow a term from Barbara Low) —a tendency which finds expression in the pleasure principle…” (55-56)

Now, again, if these are the sorts of formulations that Freud’s readers knew and accepted in 1924, then they’d have had little difficulty supposing that any violation of the pleasure principle was by definition also a violation of the constancy principle — hence “economically” mysterious.

But it is precisely Freud’s purpose at the start of the “Economic Problem” essay to question this equivalence — that is, to distinguish the two principles such that one no longer automatically entails the other. Psychoanalysis has

“attributed to the mental apparatus the purpose of reducing to nothing, or at least of keeping as low as possible, the sums of excitation which flow in upon it…“[W]e have unhesitatingly identified the pleasure-unpleasure principle with this Nirvana principle. Every unpleasure ought thus to coincide with a heightening, and every pleasure with a lowering, of mental tension due to stimulus…But such a view cannot be correct.” (413-414)

What exactly has impelled Freud to question this longstanding assumption of psychoanalysis, namely, the equivalence of the “pleasure” and “constancy” principles? He immediately continues:

“It seems that in the series of feelings of tension we have a direct sense of the increase and decrease of amounts of stimulus, and it cannot be doubted that there are pleasurable tensions and unpleasurable relaxations of tension. The state of sexual excitation is the most striking example of a pleasurable increase of stimulus of this sort, but it is certainly not the only one.” (414)

On the one hand, then, the “series of feelings of tension” do afford us “a direct sense” of the “economics” — “amounts of stimulus” — or the “objective” happenings of the inner world. On the other hand, though, the pleasurable (or unpleasurable) quality of these “feelings” is strictly speaking distinct from the “stimuli” they register, or acquaint us with. Or more precisely: the (decreasing or increasing ) quantities of “stimulus” alone cannot determine the (pleasurable or unpleasurable) quality of these feelings. More or less excitation does not necessarily generate more or less unpleasure, but something else is involved.

What this ‘something else’ is, exactly, is not so simple to say. And while Freud does raise a conjecture here, he ultimately pleads deep uncertainty. Nonetheless, it seems — again — to correspond to something “qualitative” rather than anything “quantitative”:

“Pleasure and unpleasure, therefore, cannot be referred to an increase or decrease of a quantity (which we describe as 'tension due to stimulus'), although they obviously have a great deal to do with that factor. It appears that they depend, not on this quantitative factor, but on some characteristic of it which we can only describe as a qualitative one. If we were able to say what this qualitative characteristic is, we should be much further advanced in psychology. Perhaps it is the rhythm, the temporal sequence of changes, rises and falls in the quantity of stimulus. We do not know.” (414)

Whether, in acknowledging this irreducibly “qualitative” element, Freud has conceded the inadequacy of any “economics” of mind in the strict sense — one confined to examining quantities of stimulus — is I think a question worth asking.